Chaos on Brazil’s clogged roads highlights urgent need for more rail and barge

The year 2013 is proving a disastrous one for logistics in Brazil, where a grains crop of 185mt (million tonnes), 20mt more than last year, is being harvested, writes Patrick Knight.

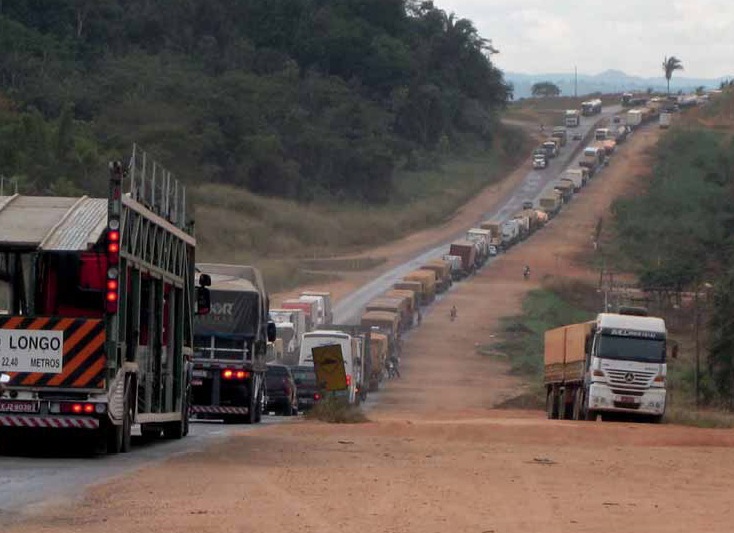

With roads clogged, ports jammed and railways overloaded, huge backlogs are building up and costs are soaring.

A 50km-long queue of trucks waiting to unload soya, corn and sugar blocked access to the port of Santos on a day at the end of May.

The port normally handles about 10,000 trucks each day. However, as result of restrictions at patios, the journey down the escarpment to Santos from Sao Paulo city took eight hours, rather than the usual 60 minutes.

During most of May as well, more than 100 ships were waiting to load grains and sugar at Santos. Some had been in the queue for two weeks, at a cost of about $45,000 in demurrage per ship each day.

Desperate to get cargoes to destinations on time, many shippers are resorting to loading low value bulk cargoes into containers and sending them to Santos by rail.

Such cargoes then leave Brazil in container ships, rather than bulk carriers, beating the queues and congestion by this means. This unlikely solution is possible because the massive inflow of consumer goods from China and elsewhere, means hundreds of containers which would otherwise leave Santos empty, are available.

So, for the time being at least, shippers get cut-price rates for grains and sugar. Coffee worth $5,000 a tonne has been carried in containers for years. But corn valued only $250 a tonne? Sounds crazy, but such is Brazil.

The congestion is adding several days to the 4,000km round trip to bring soya and maize from centre west states such as Mato Grosso to the ports. As a result, the cost of getting a tonne of soya to Santos has shot to about $150, 30% higher than last year.

This is eating into farmers’ profits at a time when the price of grains is falling.

Last year, a smaller-than-expected soya crop allowed Brazil to export 20mt of corn, a crop which in many previous years was imported. Corn exports earned a record $5 billion dollars in 2012.

Just as much corn will be harvested this year as in 2012. But the extra 20mt of soya will clog ports at least until mid August. After that, a record US corn crop will hit the market, causing prices to fall. As a result, not more than about 12mt of corn will be shipped this year and farmers face large losses as a result.

Because access to the ports in the north and north east of the country is now so poor, most of what the extra being produced in those fast growing parts of the country, has no alternative but to travel south, the great majority by road.

To ease this situation, major investments need to be made in building and improving railways, which now carry only 24% of the goods moved round Brazil. Almost 80% of that is iron ore.

If just a few locks were built and rivers dredged, the rivers could easily handle several times the 10% of the total they now do as well.

With ever more soya and corn needed by China, analysts calculate that 110mt of soya, as well as 100mt of corn will have to be grown in Brazil by 2020, 40mt more than this year.

For the past 20 years, Brazil’s complacent government has pared spending on infrastructure to only about 2% of GDP each year. This compares with the 6–7% of GDP which China spends on infrastructure.

The result has been that virtually no new rail track has been laid and nothing done to improve Brazil’s extensive waterway network, while roads have crumbled.

Brazil is becoming ever more dependent on the earnings from exports of farm commodities, notably soya and sugar, as well as meats. This has caused the government to belatedly realize that something must be done to improve logistics, if the situation is not to breakdown completely.

There is some good news. Notably, improvements on the 2,000km BR-163 road, which links the capital of leading soy producing state Mato Grosso with the Amazon river port of Santerem, are allowing access to a brand new port being built on the Tapajos river, Miritituba.

Miritituba is 350km upstream from Santarem, on the Amazon, and which now handles about 2mt of grains a year. Fleets of barges are already being moved into position to carry up to two million more tonnes of soya and corn from Miritituba to Santarem. Some of the grain will continue downstream to the ports of Vila do Conde, Outeiro and Santana, a new port being built on the channel to the north of Marajo island, in the Amazon delta.

It takes two or three days less to transport a cargo from the Amazon region to China, which now buys 70% of the soya beans shipped from Brail each year, than it does from Santos or Paranagua.

In the past 15 years, the Brazilian economy has been boosted by encouraging consumption, rather than investment.

One example of this is that 15,000 brand new cars come onto the roads each day, making already acute traffic congestion more severe.

Partly because of the horrific traffic toll, with 80,000 people killed on the roads each year, new legislation limiting the number of hours trucks can operate each day, has been introduced.

The downside of this new regulations is that journey times are taking up to 20% more than before, which is adding to costs.

Brazil is home to two of the world’s most efficient and intensively used railways, both of them operated by the Vale iron ore company and used to carry 250mt of ore from mines to the coast each year. This shows it can be done when it is essential.

Because of this example, it might be thought that it would not take long for three badly needed new railways now being built to be completed, given the urgent need for them.

But the opposite is the case and Vale’s efficient railways are very much the exception.

Work started on building the ‘North–South’ railway, which starts half way along Vale’s 900km Carajas line, in 1987. This line will eventually run more than 2,200km south through tens of millions of hectares of arable land, to link with existing lines in Sao Paulo state, then on to Parana and Rio Grande states. This will allow the millions of tonnes of corn needed to feed the flocks of chickens and herds of pigs concentrated in this region, to get there more cheaply.

But 26 years after work began, only 250km of the North–South line is operational. It is used to carry about 2mt of soya to the port of Itaqui each year.

A further 850km of track has been laid by a state owned company. But it has now come to light that because the track bed was not laid properly and drainage was inadequate, many sleepers have already rotted and embankments have been eroded.

In addition, steel rails imported from China have been found to be of poor quality, and will have to be replaced.

Heads have rolled amidst allegations of widespread corruption, although nobody is behind bars. Most importantly, however, the line is still far from ready. Much of the faulty stretch will have to be completely re-laid, at an estimated, but certainly conservative cost of $400 million.

Things are only slightly better on two east west lines, on which work started in 2007. The two 1,200km lines will eventually link the Atlantic ports of Pecem, Suape and Ilheus, with the North–South line itself. Both these lines run through important soy and corn producing regions on the way and will eventually allow new deposits of iron ore, as well as gypsum, to be opened up.

When building these lines began, it was announced with a fanfare they would be completed in three or four years’ time.

But as is usually the case, the work has got bogged down. Way leaves have not been obtained, planning permission from the ministry of the environment was now obtained, and funds have run out. Both lines will cost four or five times the initial estimates.

If these two were the only lines to be built, there might be some hope that progress might be made and that scarce resources, both financial and managerial, would be available.

But the government has now announced not only that Brazil’s first high speed line to link the countries two major cities, Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo is to be built, probably at a cost of $30 billion, a network of other high speed lines are to be built to link satellite cities to Sao Paulo as well.

As a result of this sudden enthusiasm for rail, scarce resources are likely to be thin on the ground. This is bad news for the transport of grains, which should be top priority.

A new generation of hydro-electric power stations are now being built on several of the very large rivers which rise on the central plateau where most grains are grown, before flowing down to the Amazon river, falling several hundred metres in the process.

Because of a long-standing dispute between the ministry of energy, responsible for building the power plants themselves, and the ministry of transport, responsible for navigation over who should pay, locks which would allow barges to transport grains and other goods down to the Amazon, navigable to the largest vessels, have not been built at the same time as the power stations.

The only river in Amazonia now navigable, is the Madeira, which runs close to Brazil’s border with Bolivia. Four to five million tonnes of the soya grown in western Mato Grosso, and Rondonia, travel to the Amazon ports of Itacoatiara and Santarem along this route.

But the volume using the Madeira, where no locks are needed, is limited. Again, the authorities cannot agree as to who

is to pay for dredging a river whose flow varies greatly from month to month, so which silts up. Nor can agreement be reached as to who is to install buoys which would allow the river to be used at night, and allow it to carry twice as much as it now does.

Two 30-metre locks were built at a cost of $750 million on the Tocantins river, adjacent to the Tucurui power station, Brazil’s largest, three years ago.

But several other locks must be built and rocks blasted from the river bed, if the waterway, which could easily carry tens of millions of tonnes of grains a year, is to be usable.

The Tucurui locks would have cost only a fraction of what they did, had they been built at the same time as the power station, when thousands of workers were on site.

But the lessons have not been learned, and no other locks are now being built.

If just 27 locks were built on rivers where power stations are being built or are planned, grains could be moved from farms to ports for a cost of only about $30 per tonne. This is 20% of what it now costs to get a tonne of soya or corn to Santos or Paranagua. Some soya even travels a further 1,000km south to the port of Rio Grande, an a costly option which is resorted to when Santos and Paranagua are as congested as they have been this year.

Governments in Brazil have relied on stimulating consumption, as a way of achieving growth in the past few years. Only about 17% of Brazil’s GDP is invested each year.

There is little chance of Brazil changing its profligate ways. But with industry unable to compete, it has become clear that the country will have to rely increasingly on the earnings from the commodities it can grow or mine.

To allow this to continue, much more is going to have to be spent on the infrastructure as a whole, and on railways and waterways in particular, than is now the case.

Ingram Barge Company leads the way in environmental stewardship

Ingram Barge Company (Ingram) has been a quality marine transporter on America’s inland waterways since 1946, and has grown to become a pre-eminent carrier on America’s inland waterways. Ingram owns nearly 4,700 barges; those barges are powered by an industry-leading towboat fleet, which includes approximately 150 towboats that are maintained at the highest level of standards. They transport a high volume of dry bulk commodities, including coal, aggregates, grain, fertilizer, ores, alloys, and steel products, as well as liquid bulk cargoes on over 4,500 miles of America’s inland waterways system.

As a waterways transportation business, Ingram is a company that bases its livelihood directly on natural resources. It’s always been in the company’s best interests to engage in sustainable practices and to focus on the education of future generations about the importance of protecting and preserving the nation’s waterways, from the smallest stream to the largest river. The US river system is an incredible resource that brings stability and prosperity to the global economy. Barge transportation not only supports the communities along the waterways; its economic impacts reach far beyond the river banks. Only a small portion of US waterways are being used to their fullest advantage — there remain many opportunities to harness the power of the rivers.

Remaining an industry leader in environmental stewardship is a commitment Ingram takes seriously. For its customers, this means moving more cargo over greater distances, using less energy and water, and creating less waste. For Ingram’s associates and the community, it means doing so in the safest manner as well.

As the largest carrier on the inland waterway system, Ingram feels responsibility to lead in environmental sustainability. The core values of Ingram Barge Company are: teamwork, family pride, customer satisfaction and zero harm. These values encompass Ingram’s commitment to be a good environmental steward. Ingram’s sustainability initiative, ENcompass, builds on Ingram’s past performance and charts a continued course of improved environmental operations. Ingram has developed policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of the company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities where operating, and beyond. Ingram initiatives focus on improving environmental performance and the bottom line using this environmental compass.

Ingram’s ENcompass strategy has been recognized by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the US Coast Guard (USCG). In 2010, Ingram was named the first marine transportation partner in the EPA SmartWay programme. In 2011, Ingram received the EPA’s Southeast Diesel Collaborative Award for emissions reduction innovation. In 2012, Ingram was awarded the USCG’s William M. Benkert Marine Environment Protection Gold award. This biennial award recognizes outstanding marine environmental achievements that go beyond mere compliance of industry and regulatory standards.

CEO Craig Philip is very pleased with the progress the company is making towards becoming known for its sustainable practice. “It gives me great pleasure and pride to know that Ingram has been recognized and accepted into the EPA’s SmartWay Program as one of the first marine transportation companies,” Philip said. “Ingram is proud to be on the cutting edge of developing new policies and procedures for marine transportation companies as they relate to the environmental issues at hand. Barge transportation is already the greenest and safest mode of bulk freight transport, and we will continue to lead the industry to take care of our environment.”

Ingram leads the industry by achieving environmental goals four years early! Ingram posted an 11.8% increase in fuel efficiency while moving a loaded tonne mile 73 more miles per gallon of diesel versus industry standards. This exceeds original goals set for 2017.

Ingram has partnered with diverse stakeholders committed to environment improvements, such as America’s Great Watershed Initiative, Great Rivers Partnership,The Nature Conservancy, Living Lands and Waters, and the Cumberland River Compact. Engaging stakeholders to provide awareness and understanding of Ingram’s leadership and commitment to responsible navigation, communities and the environment is helping to build a better tomorrow. Ingram has innovatively bridged the chasm between goals and principles of sustainability through action and commitment, now and in the future.

Negotiating river transport risks

Conundrum. noun: a confusing and difficult problem (Oxford English Dictionary)

“The river was even narrower now, and seemed to curl back on itself before swinging round in a series of hairpin bends. It must have been a brave man who first sent the tugs down here, with their barges out front. It was like trying to squeeze a warehouse down a woodland path. At any moment we could have become jammed fast or torn in two. The Master said that these were some of the most difficult waterways he’d ever known.” (Reprinted by kind permission from ‘Wild Coast’ by John Gimlette and available at www.profilebooks.com)

The great conundrum in river transport is neatly captured in this extract from travel writer John Gimlette’s experience aboard one of JP Knight’s push tugs on a four-river system in Suriname, South America, writes Richard Knight, JP Knight (Paranam) Ltd.

It is a simple enough question after all. ‘What is the most tonnage we can move at any one time in the largest propelled unit that still fits the least space available?’ The question becomes a conundrum because of the objective: to deliver that tonnage at the lowest cost in the safest manner with minimal or no environmental impact.

SO WHAT ARE THE LIMITING FACTORS?

On Suriname’s rivers, you can take your pick... First and perhaps predictably, there’s depth of water — or rather the lack of it. This translates as under-keel clearance, sometimes as little as 30cm; roughly the length of this page. River levels inevitably reduce in the dry season with a knock-on consequence on the effective capacity of the barges.

Grounding is all but unavoidable, loaded barges take the brunt of the damage from the mine, but on the return passage the tug’s hull is usually deeper in the water than the empty barges and keel cooling systems become vulnerable.

Then there’s tide. These are not canals, nor are they the sea; the tidal ebb and flow runs at differing speeds in differing locations. Where one river meets the estuary, another cuts across it to drive the immense body of water at over four knots up or down the Suriname River. A bar lies at the exit of one river: loaded convoys must be timed to match the window of deeper water or suffer substantial, unacceptable, delay. Those same tides also reshape sand banks, moving them bodily over a surprisingly short time, demanding constant vigilance from even the most seasoned navigator.

Wash presents a rather unique challenge. Whilst attempting to achieve the quickest passage, consideration must be given to the effects of wash. Perhaps one of the least appreciated but most important aspects of river navigation is the impact on river communities. As a convoy passes a settlement, wash inevitably finds its way ashore. Whilst a reduction in speed may be the only answer to reduce wash, some speed allows a single complete turn as opposed to the ‘back and fill’ manoeuvre favoured on the Mississippi using the tug’s flanking or forward rudders. The balance is therefore a delicate one, and of utmost importance, as those communities also operate minimal freeboard canoes ferrying dozens of school children on the same river sections. Additionally, the river bank divests itself of trees into the river as a naturally-occurring process. These are no ordinary trees. Mangrove, as any will tell you who have encountered these fibrous-rooted brick walls, pose a major threat. I have witnessed a rudder split in two by one such disarmingly slight, errant, root.

This brings me to height of eye and the view ahead. It is generally accepted that a minimum safe distance to see ‘ahead’ of and therefore over the barge convoy is two convoy lengths. Even this measure means that there is a blind spot — or shadow — of some 400 feet in the case of JP Knight’s operation. We operate one tug, known locally as the Giraffe, that has a wheelhouse as high as the tug is long. Naturally the vision forward is exceptional, but it is also rare in river transportation. On the Rhine, for example, wheelhouses are repeatedly ducking down to transit low bridges only to shoot up again once the obstacle is cleared. On our river system such compromise is not currently needed: but vision is nonetheless a major factor during night transits in the absence of any illuminated navigational beacons or shore lights. During darkness it is close to impossible to differentiate between the river, the bank and the sky unless searchlights are employed, though these tend to destroy perhaps a more valued quality; night vision.

Whilst an army may march on its stomach, in river transport it sails on its quota of sleep. River transport is as continual an activity as it is possible to imagine. This is how vast tonnages are amassed: by the inexorable accumulation of cargo day in day out. So I determined that a system of operation had to be devised that best delivered an acceptable pattern of work, audited to international standards, offering a safe operating environment to all crew members. This system, JP Knight’s safety management system, has been consistently audited by Lloyd’s Register to the International Safety Management Code since 1996 and was the first of its type in the world. It enshrined a work rhythm, written by the crews and officers themselves that ensured safe operations in any given circumstance. One and a half million nautical miles later, it still does.